Kitmondo

04 Nov 2014

This article was originally published in the April 1907 edition of “Electrochemical and Metallurgical Industry” magazine. The publication of this material aims to provide historical insight on the subject and its place in industry.

Read first part here.

Now, it is quite clear that the ultimate pressure which can thereby be produced in the furnace as result of a slip cannot be more than the pressure in the blast main, or, in other words, the pressure which produces the damage comes entirely from the blast engine. Now, a stream cannot rise higher than its source, and if a furnace casing is made otherwise strong enough to resist this pressure it will be entirely safe to reduce the size of the outlets to such an extent as to offer a material resistance to the flow of the gases from the furnace in the event of a sudden and heavy rush of blast through the furnace.

Such a checking of the gases at these outlets will greatly reduce the rapidity of flow for the moment, and will also diminish the tendency to carry solid materials out of the furnace. (In the discussion which followed the paper the following suggestive analogy was pointed out: The throttling of the gases at the outflow will reduce the amount of dust carried by them for the same reason that the waiter who pulls the cork entirely and suddenly out of the bottle will lose at least half the champagne, while the fellow who pulls it gradually will not lose a particle.)

The first blast furnace built on these principles of Mr. Kennedy was at the Iroquois Iron Co. in Chicago, but there are now in operation twenty-four furnaces of this general construction, and these blast furnaces have demonstrated, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that it is absolutely safe to altogether close the top of the blast furnace, and that the letting loose of great volumes of dust and lumps of stock at this point is entirely unnecessary.

It has been said that even if the dust is all brought down the down-comers, it will pass through the stoves and boilers, and thus be scattered over the surrounding country. Some of it of course will, if no arrangements are made to stop it, but a large proportion of it can be caught in very simple dust catchers, and since gas engines have been installed at blast furnaces, there have also been started gas washers so perfect that they will take gas from a furnace running on a mixture consisting largely of Mesaba ore and cleanse it till it has less dust in it than the ordinary atmosphere. So that given a device that brings all the gases down to the cleaning apparatus, it is entirely feasible to do away with the dust absolutely.

Mr. Kennedy concluded with the remark that there surely can be no excuse in the future for burning men on top of furnaces, or burning or otherwise injuring them with materials thrown out of the tops of furnaces because of slips, and the amount of dust sent out from a furnace will depend entirely on how perfectly the management choose to cleanse the gas by means of dust catchers and washers, which have at the present time been developed to a degree of perfection which will enable the top of a furnace draft stack to be "cleaner, as far as dust particles are concerned, than the cleanest spot in Pittsburg is at present."

Of course, all the above considerations refer only to the bad results of slips, which are falsely called explosions, and not to real explosions. They are known to have occurred in blast furnaces when blown out, and when nearly empty a lot of air possibly gets through the thin incandescent bed of fuel without being burned and mixed with the gases above, and then the whole business exploded. These are real explosions.

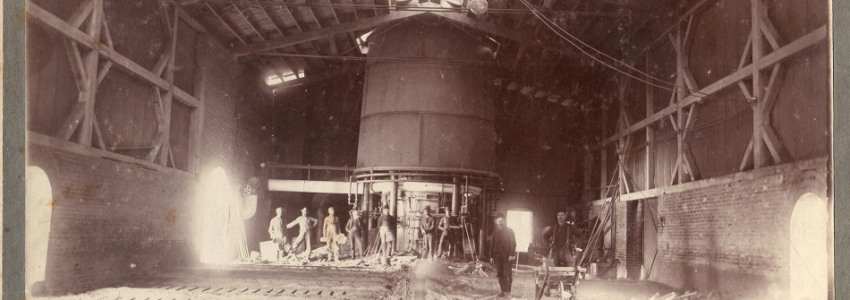

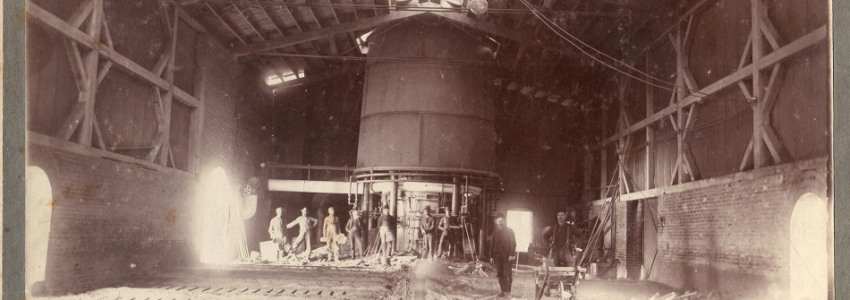

Photo Credit: Deseronto Archives