Kitmondo

12 May 2014

This article first appeared in Practical Engineering 1940 Vol1 No26. The information contained within it is accurate as of 1940. This article provides historical information pertaining to developments in Precision Engineering at the time.

The story of Joseph Whitworth, the young Manchester tool-maker who became one of Britain's most famous engineers, is full of interest for those who are at present busy in the engineering profession. Unfortunately, there are no records of the earliest details of Joseph Whitworth's life and the story of his career is particularly detail-less when it comes to his setting up his first tool-making business in a small shop near the centre of Manchester.

All we know concerning those early years is that Whitworth's first Manchester venture was extraordinarily successful and that, after he had been established in his shop for a year, he moved to larger premises alongside the Rochdale Canal. Shortly afterwards he leased a suite of offices and, within the space of a few years, his tool-making works underwent still further expansion and gradually overflowed, as it were, into the surrounding property.

A Man of Vision

Whitworth, from the time he first set up in business, knew what it is to meet with success. Hardly an inventor, hardly an industrialist, ever existed whose life-history shows a record of more continuous success then does that of Joseph Whitworth, "Tool-maker from London." Included among the elements of Whitworth's success was certainly the propitious time in which he lived, but, of more significance than that, perhaps, was the fact that Whitworth was not an ordinary trained mechanic content with the making of a good living and the building up of a successful business.

He was, on the contrary, a man with a vision, an individual whose ideals rose far above the engineering customs of his day and, withal, a skilled mechanician whose penetrating insight into engineering matters enabled him to realise the many constitutional defects of mechanical practice and, ultimately, to eliminate them.

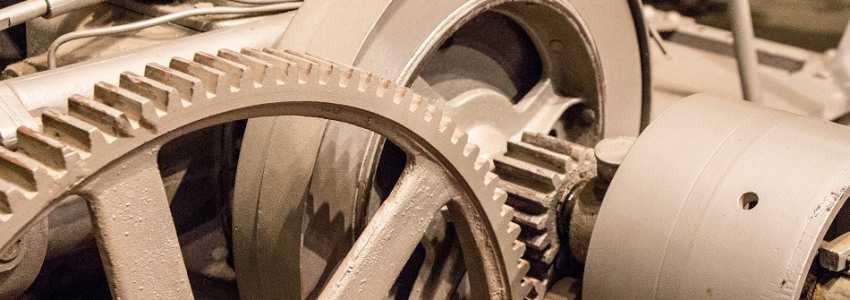

They call Sir Joseph Whitworth— he received his baronetcy in later life— the "Apostle of Engineering Accuracy," and a truer title than this would be impossible of creation. Before the rise of Whitworth, engineering standards were practically non-existent. As. regards the dimensions of small and interchangeable parts, such as nuts and bolts, various screw threads and so on, the entire engineering industry was in a hopeless state of confusion. Each engineering works possessed its own system of screw thread, each individual tool-maker, in fact, worked to standards of his own making.

A Formidable Obstacle

The total lack of any system of standardisation of mechanical parts and components proved a great obstacle to the early engine makers. George Stephenson, for instance, and, before him, James Watt and other engine-builders, lamented the fact that, when undertaking the repair of their engines, they were not able to get nuts and bolts to fit the replacement parts. Thus, in those days, if you wished to effect a repair to a piece of machinery, you were faced with the task of making your own nuts and bolts and of forming your own screw threads. Engineering standards had not been established.

Joseph Whitworth, the individual who introduced a new era into engineering practice, was born at Stockport, near Manchester, on December 21st, 1803. At the age of 14 he entered his uncle's cotton mill at Leeds with a view to learning the business and becoming a partner in the concern. Within a year or two, however, Whitworth left the business, finding that he had no taste for it, and he managed to procure a number of temporary jobs at various engineering foundries in and around Manchester. Later, he left for London and, after obtaining a position in Maudsay's foundry at Lambeth, he served a form of assistantship with Messrs. Holtzapffei and Clements, who were famous London toolmakers.

It was after this period with Holtzapffei and Clements that Whitworth set up for himself in Manchester. Business in the engineering world of that day was good. Machine parts were becoming more and more in demand. The country, as one writer put it, was growing "machinery mad."

Introducing Surface Plates

Whitworth's passion for accuracy in engineering measurements was formed during the early days of his mechanical training. He grew to hate the rule-of-thumb methods which so greatly prevailed in the machine shops of the period. His business, young Whitworth vowed, should not be dominated by rule-of-thumb devices and practices. The tools and machine parts which he turned out should be constructed, as far as possible,-to accurate dimensions, and he would endeavour to devise satisfactory methods of working to such degrees of accuracy.

The first invention of Whitworth was his method of making true planes or surface plates. Previously, such planes had been made by rubbing two approximately flat surfaces together with abrasive material between them. Whitworth showed, however, that such a method of making true planes could never succeed satisfactorily and that usually it merely rendered the surfaces more inaccurate than they were in the rough. He showed that the better way of preparing these plates was by mechanically scraping away the "high spots" from the surfaces. By this means he was able to make surface plates of such a degree of flatness that if two were gently squeezed together so as to exclude the air between their surfaces, they remained in firm contact by virtue of the external atmospheric pressure, and it was often very difficult to separate them.

Whitworth's name is undoubtedly most deeply associated in the mind of the modern mechanic and engineer with the system of standardised screw threads which he introduced. In a paper which he read before the Institute of Civil Engineers in 1841, Whitworth outlined his proposed system of thread sizes and made an appeal for a greater degree of standardisation and of accuracy throughout the engineering industry.

The time was ripe. Little opposition to the idea of standardised screw threads was encountered and, within a year or two, the standard thread sizes introduced by Whitworth were in daily use all over the country. The chief railways immediately adopted his standardised system of thread-cutting and the Royal Dockyard engineering shops embraced the system with almost visible enthusiasm.

Measurements and Armaments

Previous to his introduction of standard threads, Whitworth had realised the necessity in some departments of engineering of having some means of measuring with great accuracy the distance between two plane surfaces. In consequence, he developed a new form of measuring machine, an instrument which was able to measure distances with a hitherto unheard-of accuracy. A machine measuring distances with an accuracy of one ten-thousandth part of an inch was turned out by Whitworth in 1833. These delicate measuring machines occupied a great deal of Whitworth's attention. Ultimately, he produced a machine which he claimed was capable of measuring a distance of a millionth of an inch. This masterpiece now reposes in the Science Museum at South Kensington, London. Its delicacy of measurement is, of course, beyond all practical requirements, and it is consequently more of theoretical than of practical interest.

In the October of 1853, an event occurred which brought still greater fame to Whitworth and, incidentally, unbounded profits to his business. This was the outbreak of the Crimean War. Whitworth branched out as an armament manufacturer. At the request of Lord Hardinge, the Army's Commander-in-Chief, he began to build rifle-making machinery. The Government of the day urged him to investigate the whole subject of rifle construction and, if possible, to devise a better and a more efficient type of rifle than that which then existed. As a result, the celebrated "Whitworth " rifle arose. It was officially tested against other makes of rifles and, for accuracy of aim, efficiency and general construction, it scored over all competitors. Whitworth rifles and, later, cannons made in the Whitworth works, were shipped overseas. The accuracy which Whitworth had introduced into engineering and machine construction methods had, it was found, uses in war-time as well as in the days of peace.

The Whitworth Scholarship

In 1868 Whitworth founded the scholarships which are named after him. He gave annually a sum of £3,000 for scholarships to be awarded for "intelligence and proficiency in the theory and practice of mechanics and its cognate sciences." In the following year, Whitworth received his baronetcy, and it was not long before he retired from active participation in engineering practice.

Sir Joseph Whitworth died at the age of 83, on January 22nd, 1887, at Monte Carlo, where he had been residing in consequence of his indifferent health. The great proportion of his fortune he left to trustees. £100,000 was left by Whitworth for the permanent endowment of his scholarships.

To the end, Whitworth retained his love of accuracy. It is related, for instance that, in a spare moment, it occurred to him that the action of an ordinary pair of scissors in which one blade was slightly bent over the opposing blade was mechanically incorrect. In an endeavour to prove his contention, he made a pair of scissors, the blades of which had perfectly flat surfaces, were set parallel and slid over each other in true contact.

Whitworth's "ideal" scissors, beautifully made though they were, had one point of disadvantage. They would not cut! Thus, for once, at any rate, was it demonstrated that inaccuracy of construction gave more practically satisfactory results than the ideal accuracy of perfect mechanical creation.

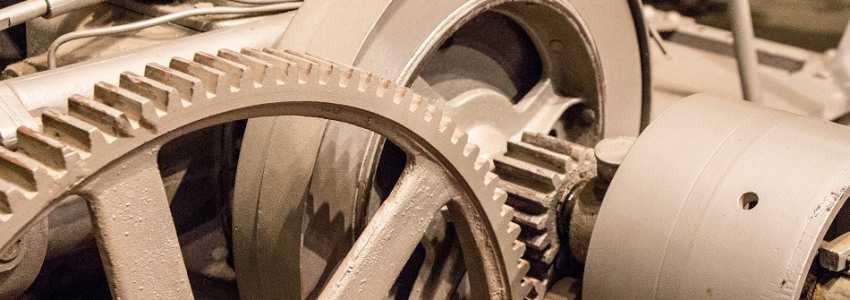

The Spring Wheel

One of Whitworth's lesser-known productions was the spring wheel which he invented. This he produced in several different forms. Spring wheels are those in which circular or band-shaped springs take the place of spokes and serve to absorb the shocks on the rim of the wheels. The introduction of the pneumatic tyre made spring, wheels un-necessary for ordinary vehicles. Nevertheless, there are technicians who assert that spring wheels still have their uses and that, very probably, this old invention of Whitworth's may see considerable development in the future.

It is interesting, also, to note that, during the last war when rubber was practically unobtainable in Germany, many of the cycles left by the German armies during their final retreat were found to be equipped with spring wheels similar to those originally devised by Sir Joseph Whitworth 80 years previously.

In habits, Whitworth was slow and painstaking. He seldom took anything for granted. New notions, novel ideas which occurred to him, facts, contentions, theories—all were submitted by him to careful examination before they were finally accepted.